"Like Singing a Song" About the Most Magical Father I Never Met

In my experience, fathers tend to fall into two general camps. There are the dads so preoccupied with their own interests and careers and financially supporting their families that they rarely interact with their kids. Then there are the dads who strive for an active role in their children’s lives: They change their diapers and teach them sports, counsel them as they grow up, and worry about their futures.

But then again, imagine a father who would write an operetta for his children, with partsfor each to sing to fend off homesickness when they’re far from home. In the 1930s, Britishcivilian officer Alfred G. Bird was just such an extraordinary dad. Tragically, as I learnedthrough an accidental pen pal, this creative and doting father’s life ended in a wartimecrime that took decades to uncover.

First, the tragedy of Maj. Alfred G. Bird

I was researching India’s remote Andaman Islands for my novel Glorious Boy when I first encountered Maj. Alfred G. Bird’s name. A civilian officer who served as an aide to the British colonial commissioner, he at first seemed little more than a bureaucratic footnote in this strange outpost’s history.

Port Blair, the Andaman Islands’ only town, was founded by the British in the late 1880s as a penal colony for Indian independence fighters. Carved out of dense primeval forest, with more than 400 miles of ocean to the coast of Burma and nothing but trees, swamp, and hostile tribes in the rest of the archipelago, the colony more than earned its nickname “Black Water.”

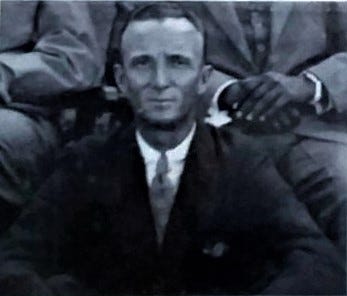

Bird was posted to this grim place as a supply officer in the 1920s, and he lived there for more than 20 years. The only reason he caught my attention was that the Japanese, who occupied Port Blair in World War II, executed him.

As a civilian, Bird should have been safe in Calcutta on May 5, 1942. But he’d stayed in Port Blair to assist with the final evacuation of British Indian military personnel — an evacuation that never happened. The expected ship was torpedoed, and before another could reach the islands, the Japanese landed.

Bird was among the first to be rounded up and imprisoned. Then the Japanese commandant executed him as an example to the local population.

Not only did Bird’s brutal murder — a beheading — violate the Geneva Conventions, but this war crime seemed to embody the uniquely barbarous complexity of the Andamans’ colonial history. The accuser whose false testimony sealed Bird’s death warrant was an Indian convict and murderer who’d been jailed by the British and then collaborated with the Japanese. Most of the other local Indians in Port Blair liked and respected the major, but they didn’t dare defend him. This all made Bird an important character for my novel.

Yet in the 17 years it took me to complete writing Glorious Boy, I could find little more about Bird than the facts surrounding his execution. I knew next to nothing about Alfred G. Bird the man, other than his popularity among British and Indians alike.

I imagined him as a bachelor. Boy, did I get that wrong!

Alfred G. Bird, grandfather

After my book was published, I belatedly came across a webpage devoted to Maj. Alfred G. Bird. One critical detail took me by surprise: Bird had a grandson. That grandson’s name is Chris Pratt-Johnson, and he’d created the tribute site.

I emailed Chris, and he promptly wrote back. Over the next few months, as our messages flew between my home in Los Angeles and his in Spain, I grew to know and love his grandfather. The real Bird was more complex and vastly more endearing than I’d imagined.

Though both his parents were British, Bird himself was born in India. This made the subcontinent his homeland, and he seemed to have a deep and abiding connection that held him there. As a young man, he served in the Indian Army Reserve Officers. Then he married Chris’ grandmother, Maisie, who also was born and raised in India.

Maisie was 19 and Alfred was 24 at the time of their wedding. Within a few months, they were off to the Andamans, where they would raise five children. Chris’s mother, Nell, was the eldest, followed by Maisie, Heather, Max, and Rosemary.

“They adored their father,” Chris told me, and when he shared the family’s lone surviving letter from Bird, I could easily see why.

“Like singing a song”

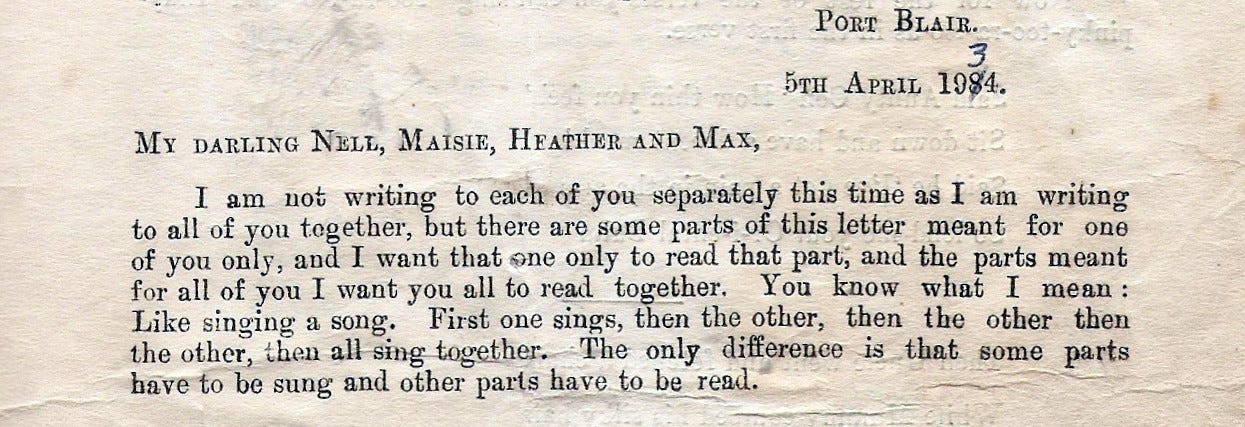

A single letter might not seem like much of a basis for judging a man’s character, let alone for falling in love with him. But I can honestly say that I’ve never read another letter like this one. It speaks volumes, not only about Bird’s concern for his children but also about the closeness and fun they all enjoyed when they were together. If I’d ever received such a letter from my own father, I would have swooned.

Written almost exactly eight years before Bird’s death, the letter is addressed to his four oldest children, who, like most kids of British officials during the Raj, were sent to boarding school in England at a young age. That policy might sound harsh, but Bird’s letter suggests that he missed his kids every bit as much as they could possibly have missed him. The only one of his children still at home in Port Blair at the time was Rosemary, then age two.

Not only was England nearly 6,000 miles away, but it took five weeks or more for mail to make the journey. And only one mail ship a month landed in Port Blair. After 20 years in the islands, Bird clearly understood the excitement that a single letter could engender, and he made the most of it by turning the contents into an event for his children to perform, perhaps many times over, in their faraway dorms:

My Darling Nell, Maisie, Heather, and Max,

I am not writing to each of you separately this time as I am writing to all of you together, but there are some parts of this letter meant for one of you only, and I want that one only to read that part, and the parts meant for all of you I want you all to read together. You know what I mean: Like singing a song. First one sings, then the other, then the other, then all sing together.

What follows is a script that would have done Gilbert and Sullivan proud. Bird assigned lines to each of his children that set the stage and launched a story guaranteed to remind them just how odd, unpredictable, and welcoming their large family would always be. The play was like a virtual snapshot of their household in Port Blair but less scary and a lot more fun.

For Nell — Fancy a man walking in by the side door while you were at school and saying that he had a hurt arm!

The intruder in Bird’s story doubtless was one of the local convicts who lived and worked around the port after their release. Nothing to be afraid of, Bird assured his children. In fact, he invited them to sing the story to the tune of “Mademoiselle from Armentières”:

A man once walked inside our house, Too-ra-loo

He tip-toed gently like a mouse, Too-ra-loo

Said Aunty Con, “How do you do?”

Said he, “Quite well, the same to you”

Inky-pinky-too-ra-loo

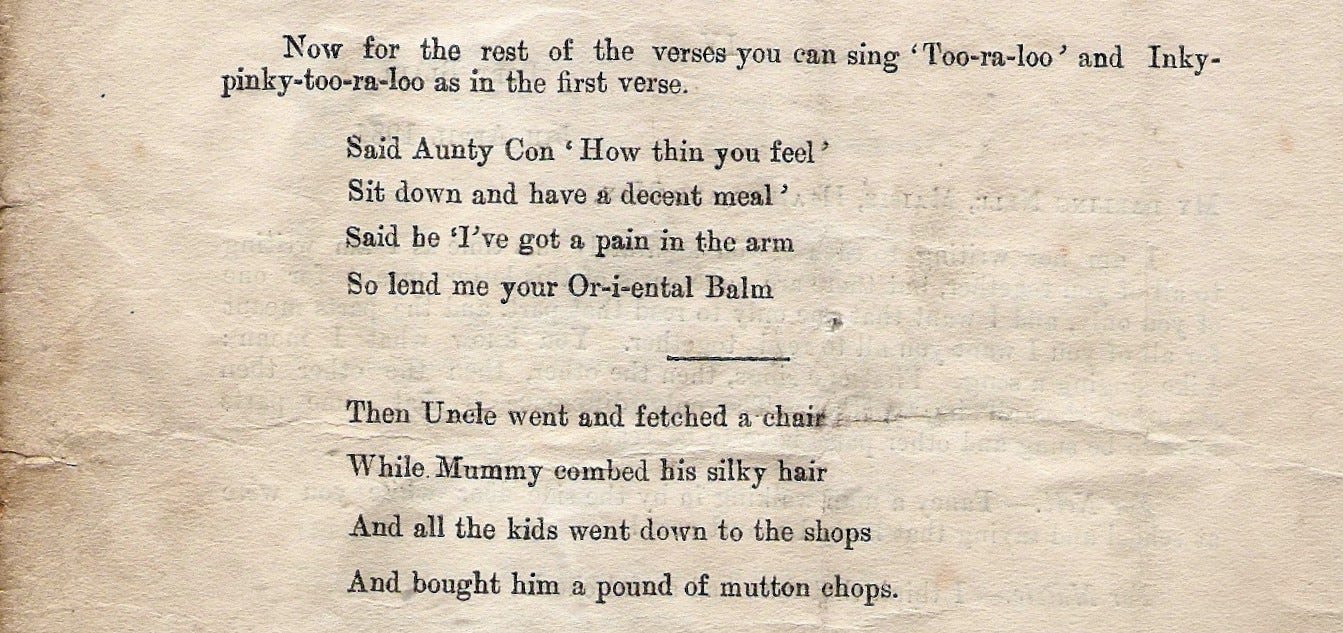

Bird then threads every member of the household back home into the tale he’s spinning. Little Rosemary falls to the ground as the kids dance in their excitement over the stranger. Aunts, uncles, and cousins cluck over the man’s fake injury. They bring him mutton and feed him curry and tell him a joke or two.

And just when everyone’s having a grand old time, the plot twists — as all good stories must — and Bird gets to the part that he knows his children will enjoy best of all. The intruder vanishes!

Suddenly May came wobbling in

And said, “Begorra that’s a sin

Stop that man, for he’s a thief

He’s walked off with our roasted beef!’”

Bird delivers the denouement in his own voice, both confirming and reassuring that this is not a fictional account but just another wild, wacky, whimsical event in the life his children have left back home — and to which he can hardly wait for them to return.

Well, that’s all. There was an awful row afterwards, But I can’t tell you more about it because the mail is just leaving.

Cheer-O my darlings. Heaps and Heaps of love to all of you. Please don’t show this song to Gracie Fields because she will only sing it at the Palladium and I don’t want everybody to know about it.

Your affectionate

Daddy

The lost father

Bird’s wife, Maisie, and 10-year-old daughter, Rosemary, last saw Bird on March 13, 1942, the day they were evacuated from Port Blair. As he waved goodbye from the jetty, they stood on the deck of the S.S. Norilla expecting to be reunited with him in a week or two. Instead, just nine days later, the British in Port Blair surrendered to the Japanese without a shot, and Bird’s fate faded into a blur.

For nearly 60 years, the family had no idea what had become of their beloved father. And the British government didn’t tell them. This was the truly heartbreaking twist in the story that Bird never got to tell his children.

In 1947, two years after the war ended, Bird was presumed dead, and his estate went through probate. But the family was given no cause of death. Their first glimmer of truth came through another family’s Asian saga, The Golden Oriole, published in 1987. A single paragraph in that 600-page tome mentioned Bird’s execution by the Japanese.

“Nobody in my family including his five children had any idea that he had been executed,” Chris told me. “So I decided to research the event to see if the accounts in the book were factual.”

That search finally took Chris to Port Blair in 2003, where he discovered the same archives that I used in my own research. Still, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission back in London refused to confirm they knew anything about Bird’s murder.

Then, in 2017, the plot thickened. A research fellow with the Singapore War Crimes Trials Project contacted Chris to ask about his grandfather. It seemed that right after the war, two low-level lieutenants had been convicted of participating in Bird’s murder. The trial was conducted by the British military, yet no one ever notified Bird’s family that he’d been killed.

Armed with this “new” evidence, Chris finally convinced the War Graves Commission to add his grandfather to the Civilian War Dead Roll of Honour 1939–1945, but the commemoration came far too late to bring closure for Bird’s widow and children.

At first, Chris dismissed the notion that there had been a cover-up. He thought his grandmother must have known but wanted to spare her children the traumatic details of their father’s death. Then Chris learned of a 2008 BBC investigation into another group of war crimes victims whose families were kept in the dark. The Japan Times coverage of this expose concluded:

British ministers, anxious to end the war crimes trials in 1949 and rebuild relations with Japan, appear to have concluded it was best not to reveal to the relatives of the deceased how their sons and husbands died.

“So,” Chris realized, “it’s possible my grandmother didn’t know.”

If so, she died not knowing and so, most likely, will the last of her children. Chris’s Aunt Rosemary is now 89. The younger members of the family have decided to leave her enchanted memories of her extraordinary daddy undisturbed. I can’t say I blame them.

Inky-pinky-too-ra-loo…